Being a white rapper since the early 90s has been a really mixed bag of confusing race politics; I think it gives me a different perspective. Hip-hop is a black art, white supremacy reigns, so what can I do to undermine it even though I have benefited from it? I do end up having a lot of discussions about race, and in today’s hip-hop environment there just isn’t a deep enough in depth discussion about race – or any type of politics at all really. Early Sole quotes like, ‘The white man’s the fucking devil,’ I’m sure helped weed out some fucked up white people in the beginning of my career, but people still say and think some stupid shit. I’ve gotten into a lot of intense discussions both online and at shows with people, sometimes it goes badly and I alienate them but I’d like to think I’ve helped civilize more of my white brethren then [sic] I’ve alienated. My supporters are not typical white rap fans though, for the most part they get it. In my field I can never stop thinking about race. As a white rapper I gotta own my shit; my bloody heritage. – Sole, interview with It’s Going Down: Daily News of Revolt Across the US, Canada and Mexico, August 15, 2015

I got that white privilege / Wanna use it for what it’s worth / Bring it to the face of corrupt ass cops / And wannabe cops who kill whoever they want / And when they get caught all they get is a couple days off / If Zimmerman’s saying he carried out God’s plan / Then God’s a white racist / God is outdated / The preachers serve the state / So don’t talk to me about hate / It’s all tough love / I know what side I’m on – Sole and DJ Pain 1, “Don’t Riot”

In the volume, Everything But the Burden: What White People Take from Black Culture (2003), contributor Carl Hancock Rux offers a critical response to Norman Mailer’s 1959 essay, “The White Negro,” in which the white social critic essentialized blackness as a site of expressive sexuality and anti-authoritarian cool that defies white rigidity, yet which can be taken up by the white hipster in his turn toward black primitivism as a survival strategy in a totalitarian era of existential angst.[1] Rux notes that what constituted hipness in the mid-twentieth century, constellated as it was around a caricatured blackness in the white American imaginary, is now articulated through a hip-hop stylized blackness associated with rebellion and located in the urban ghetto.

His key insight is that white performances of blackness as emblematized in the super-stardom of “new white negroes” such as Eminem says more about whiteness than it does about blackness, particularly in terms of how whites deploy race to perform disposable racial identities. (Indeed, that does say something about the supremacy of whiteness!) In this way, race difference is decontextualized, depoliticized and, in some ways, deracialized (i.e. rendered blind of itself) in a commercial landscape where blackness can be taken up by non-blacks without the burden that race signifies in the experiences of blacks themselves (à la Jones 1963).

In a word, Rux writes that the “new White Negro—like Eminem—has not arrived at black culture…He has arrived at white culture with an authentic performance of whiteness, influenced by a historical concept of blackness.”[2] What Rux is arguing here is that Eminem represents dominant white culture’s representation of comical, surreal, primitive blackness that, despite Eminem’s having been socialized as black, only works to replace black culture with a re-imagined whiteness[3] that decontextualizes the whole concept of race at the same time that it reinforces it as a category of identity. In this way, white rappers like Eminem can borrow from and identify with black culture without taking responsibility for the actuality of race as a lived experience of difference for those marked as non-white.

Rux’s insights proffer a sobering check on unexamined white identifications with black culture and indeed throws into a crisis of meaning the act of appropriation—as well it should. Taking Rux seriously, this essay examines one white rapper’s performance of musical blackness in order to map the salience of whiteness in his identification with hip-hop as a “black art.” However, it does so in a way that is more optimistic than Rux in its outlook on the issue of white cultural appropriation. A contextual line of approach to hip-hop that recognizes its ties to black self-fashioning as well as its circulation in crossracial contexts allows us to consider the possibility that appropriation can function as more than an act of cultural theft.

When done self-reflexively, appropriation can work as an act of cultural contribution (Neal 2005). Similar to what Gayle Wald says of Janis Joplin’s appropriation of black blues women’s sexuality in her self-fashioning as the impolite, transgressively female alter-ego “Pearl,” there are white performers (or, in the case of Sole, rappers) who reflect “an ambivalent dissidentification with whiteness” through what George Lipsitz calls “discursive transcoding”: “or the process by which white artists ‘disguise’ their own subjectivities in order to ‘articulate desires and subject positions’ that they cannot express in their own voices.”[4]

White MC Sole in many ways embodies this process insofar as he looks to black culture, via his immersion in hip-hop, as a “source of cultural self-fashioning” because it has “nurtured and sustained ‘moral and cultural alternatives to dominant values’ and served as an ‘important source of education and inspiration to alienated and aggrieved individuals cut off from other sources of oppositional practice.’”[5]

This is particularly evident in Sole’s later work with The Skyrider Band and DJ Pain 1 as well as in his Nuclear Winter mixtapes.

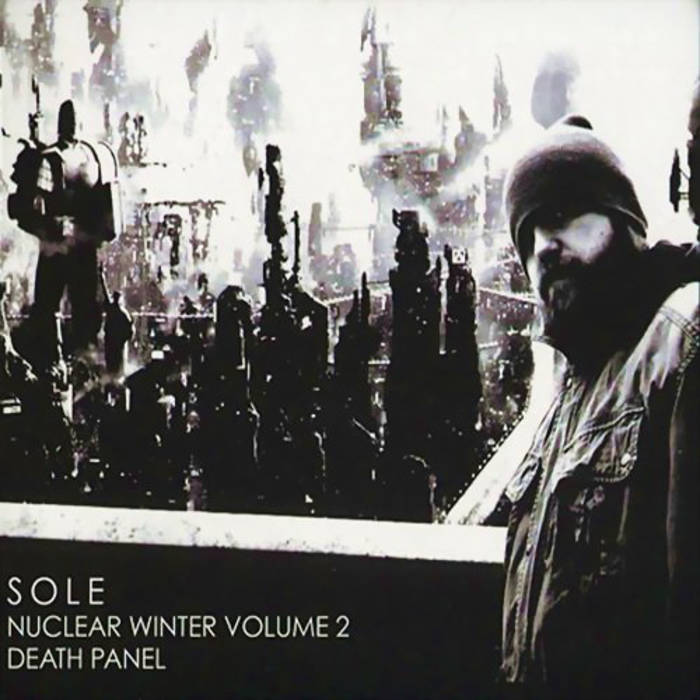

Released as free downloads on September 11, 2009 and January 12, 2013, respectively, Nuclear Winter Vol. 1 and Nuclear Winter Vol. 2: Death Panel signify a more deliberate gesture toward art as agit-prop in Sole’s musical output. Taking tips from Debord, whom Sole cites as a major influence on his own intellectual formation, the rapper engages in an act of détournement (French for “rerouting” or “hijacking”) as part of a radical anti-capitalist critique and deconstruction of the Debordian “society of the spectacle.”

As part of Sole’s efforts to dismantle the spectacle, the artist deploys a technique known as détournement, developed by a mid-twentieth century, Paris-based collective of radical artists and theorists that Debord founded called the Letterist International (LI), out of which emerged the Situationist International (IL).[6] Also a radical collective of artist, theorists, and philosophers rooted in Marxism, Dadaism, and surrealism, the SI believed in the spontaneity of the moment and saw in it the opportunity for creating “situations”—that is, artistic practices for political purposes. Hence the term, “situationist.” As part of this practice, situationists exercised détournement by which they turned “expressions of the capitalist system and its media culture against itself.”[7] This involved emptying the expressions, seen as political slogans, of meaning and reinscribng them in a way that deconstructed the capitalist discourse embedded in such expressions.

Playing on the consumerism that infects much of the hip-hop culture industry today, reflective of society as spectacle, Sole conceived of the Nuclear Winter project as a situationist prank by which he took the beats produced for big-name icons in the world of mainstream hip hop, in particular, and pop culture, in general, and rapped over them with scathing indictments of U.S. capitalism, militarism, and statism. It signifies a methodological mash-up of social theory and cultural criticism inspired by the work of Noam Chomsky, Emma Goldman, Guy Debord, McKenzie Wark, Malcom X, and Slavoj Zizek served over “commercial rap” bangers that get the head nodding as much as they get it thinking by way of Sole’s insertion of deftly layered lyricism.

One example of this is “White Rage.” Co-written with journalist and white rapper Pedestrian, the song signifies on the trope of “black rage”—a term that gained popular usage in black nationalist parlance of the late 1960s and which refers to the anger some American blacks feel in the face of the dehumanizing forces of systemic racism and white supremacy. In this, Sole deconstructs the discourses of white supremacy as they manifest in white discontent with a black presidency; white anger at the influx of migrants from parts farther south of the U.S.-Mexico border; and white anxiety about black criminality. Described as “a response to the Tea Party, race baiting,[8] and the insanity that has infected white America” in what Sole identifies as a “post-Obama era,” this détournement of Virginia-bred rap duo Clipse’s radio hit “Popular Demand” renders the populist frenzy of the Tea Party movement absurd while implicating it in a larger structure of white supremacist capitalism.[9]

The song closes with a sermon entitled “Arizona Goddamn” that Pedestrian, in his rap alter-ego as Evangelist J.B. Best, delivers with the fiery zeal of a Southern preacher. A variation on the late Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” the piece is an angry response to the absurdity of anti-immigration and anti-migrant fervor in the U.S. as evidenced by legislation (Arizona SB 1070) in 2010 for increased surveillance of the U.S.-Mexico border. This is cast against the backdrop of the attempted assassination of Arizona Representative Dem. Gabrielle Giffords who did not support the law’s passage under Republican Governor Jan Brewer.[10] A subtextual analysis of the song’s lyrical content in conjunction with a reading of its performance as music video[11] further illuminates the ways in which critical whiteness is operating in Sole’s work, particularly this lyrical jab at the “new patriotism” (Lipsitz 2006) of the American political landscape.

Directed by John Wagner, the video is set just outside of the Colorado State Capitol building, looming on the horizon as the piece begins. The camera then pans in on what appears to be a protest in which a small handful of people are waving placards that don: 1) neoconservative political slogans making conspiratorial claims about the government: “Pelosi Traitor Soros Oil Spill”[12] and “9-11 was an inside job / They outsourced”; 2) raced, if not racist, statements about national borders and territorial ownership: “This land is my land!”; and 3) an implicitly anti-black defense of whiteness in a variation on the trope of Reaganomics: the word “Obamanomics” is scrawled above a drawing of what looks like the mythical Eye of Horus[13] beneath which are the words, “White Slavery.” Other signs read: “Adam and Eve were white”; “It’s not global warming…”; “California is not part of my country” (with a drawing of the state filled in with the colors of a rainbow); and “Free Trade Not Free Loading Immigrants”—all signifying the possessive investment in whiteness as manifested in the neoconservative agendas of white supremacist biblical literalism, anti-environmentalism, anti-gay homophobia, and anti-immigration xenophobia as well as neoliberal free market capitalist ideology, respectively. Amidst this small swarm of protestors, Sole, donned in the formal attire of a corporate businessman or government official-gone-underground hip-hop-insurgent, raps the verses to “White Rage” as the video sequences between shots of him performing solo on the steps of the Denver Capitol Building and before the small gathering of protestors beneath a statue of a gun-toting pioneer—a symbol of American frontierism and the colonization of Native American soil.

With a situationist’s concern for the fierce urgency of the moment, Sole released the self-produced video “immediately after it was finished and as quickly as possible.”[14] The song itself, meant as a an “experiment of rap journalism,”[15] begins with questions directed at white discontents: “I know you hate him, don’t you? You’re paid to hate him, aren’t you?” Underlying the question is a subtle jab at the right-wing conspiracy theorists and naysaying politicos who deride President Obama as part of a conservative backlash of an agenda aimed at rooting out of the Oval Office anyone left of center (or who is threatening to white normativity for that matter). In this way, Sole engages “White Rage” as a signifier of “whites in crisis” who “find greater cultural correspondence with right-wing racial codes and articulations of racial anxieties.”[16] Believing that a “conspiracy of antiwhite minorities and multiculturalists is repressing their free expression of a white identity,” Whites who subscribe to such codes resort to a paranoid racial politics that “fans the flames of white anger against non-Whites and ups the ante of racial hostility.”[17]

Fully aware of these “whites in crisis,” Sole segues into the song’s hook as he raps:

White rage

Won’t be white saved

By white collar criminals

In white capes

Running old school border paranoia campaigns

In Willie Horton’s nameWhite man you need someone to blame

Welfare nightmares

In vicious votes they wakeWhite man you need someone to blame

Here Sole once again takes aim at the figurative “white man”—a metonym of white racial domination secured through the workings of government subsidized big business (i.e. the mechanisms of corporate welfare as manifest in the Wall Street bailouts), symbolized by Sole’s reference to “white collar criminals” who, by dint of their part in constructing a system of free market capitalism that exploits racial minorities, are likened to Ku Klux Klansmen draped in “white capes.” Sole then implicates this system in the failures of welfare reform (read: “welfare nightmare”), which government officials have instigated through poor funding while shifting the burden of responsibility (read: “White man you need someone to blame”) on those most disenfranchised by welfare budget cuts: poor African-Americans and Latinos/as.[18] At the same time, it addresses the welfare nightmare that is the Wall Street bailout, which served only to solidify the problem of economic inequality in this country.

In order to drive the point home, Sole invokes the name of William R. “Willie” Horton, an African-American convicted of felony and sentenced to life in prison without parole. [19] As part of a Massachusetts weekend furlough program, he was released from prison and did not return, subsequently committing assault, armed robbery and rape.[20] In the 1988 presidential campaign, Republicans tossed his name around as a means to bolster opposition against then Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis who supported the furlough program as a method of criminal rehabilitation.[21] Sole signifies on this mudslinging, or “race baiting”—which results in racial profiling and an unfounded conflation of Willie Horton’s blackness with criminality—by suggesting that much of the paranoia fueling the formation of the American police state is predicated on racist assumptions about who can and cannot have access to American citizenship. Such paranoia is part and parcel of a discourse of whiteness that reads the world through the lens of white innocence.

Sole meanwhile turns “white rage” against itself by stating that it won’t be “white saved.” That is, those from whom the malcontent of white America are seeking solutions are in fact part of the problem. Sole makes this clear as the song goes on:

Your boys Reagan and Clinton deaded the unions

Jobs bounced south, while Mexico fed on

Cut-rate red state corn, come on,

That’s trickle-down,

Prolific earth deserted, they went North

To do the shit work you now slur ’em for

Here, in true hip-hop fashion, Sole implicates past U.S. Presidents Ronald Wilson Reagan (1981-1989) and Bill Clinton (1992-2000) in the present economic woes that those afflicted by “White Rage” are decrying. Both of their presidencies engaged in domestic and foreign policy practices that greatly contributed, in the long-run, to an increasingly desperate system of economic collapse and post-industrial urban decay. Reagan’s system of “trickle-down” or “supply-side” economics—also euphemized as “Reaganomics”—entailed a decrease in taxes on the wealthy and subsequent cuts in social programs for the poor and working class in light of wealthy tax breaks. [22] This lead to the further impoverishment of lower-class urban communities already disenfranchised as a result of an outsourced manufacturing industry, co-opted by transnational corporations.

Clinton’s presidency meanwhile ushered in the finalization of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which facilitated the boom of corporate agribusiness and commissioned the outsourcing of industry to parts south of the U.S.-Mexico border. This has resulted in the exploitation of cheap labor in Mexico as well as the destabilization of local infrastructures, especially local agriculture, as U.S. agribusinesses, with the unregulated freedom afforded by NAFTA, are exporting corn to Mexico and there selling it at a price with which local farmers cannot compete. Without a livable wage, workers and their families have been effectively forced to migrate North without documentation, only to be subjected to a system of wage slavery, hyper-bureaucracy, hyper-surveillance, racist social stigma, and anti-immigrant bias that provides them scant access to social mobility and little to no access to ownership over the means of production.

As Sole notes, this is all part and parcel of “trickle-down,” which leads him into his next verse: “This bullshit about big government / Like it’s what the problem is / Who’s gonna pay your kid to go shoot at Arabs then?” Using their language against itself, the rapper “calls out” those who complain about “big government” for being the very ones responsible for “big government” in the first place. In asking the question, “Who’s gonna pay your kid to go shoot at Arabs then?,” Sole is implicating opponents of big government, namely Tea Party populists, in a system of big government that is predicated on a style of “Americanness” (read whiteness or white Americanness) that sees support for U.S. military interventionism as a matter of patriotic duty to the state. Yet by way of public support for the capitalist war machine from neoconservative populist groups such as the Tea Partiers, the American government has funneled billions of tax dollars into police efforts in the Middle East that are incited by xenophobic assumptions about the non-American (read: “non-white”) other as generated in a racist American imaginary—one which Tea Party populists help shape. As a result of such spending, however, the government has increased the burden of taxation that opponents of big government—who are at the same time proponents of the unhumanly expensive “War on Terror”—are protesting. Sole in this way does well to call our attention to the irony and contradiction in such protests against big government.

To this Sole adds:

If that sounds elitist, my bad, I’m defeatist

Them wars in the East is

Unwinnable, ceaseless

Only Lockheed Martin

Knows what their meaning is

Recognizing the dire consequences of intervening in a political situation for which the American public as well as its so-called representatives in government have no context, Sole sees the futility of war, particularly as it has been launched in the Middle East where an already unstable infrastructure—in no small part due to U.S.-backed economic sanctions as well as the CIA’s sponsorship of corrupt politicos—has become further destabilized. Weapons manufacturers such as Lockheed Martin meanwhile have a stake in the war as they generate capital for the military industrial complex of which they are a key part. And so the “War on Terror,” which is nothing more than a political slogan betraying an anti-Arab propaganda, rages on, “unwinnable, ceaseless.”

The above verse then segues into an indictment of corporate lobbyists as part of Sole’s larger critique of free-market capitalism. Specifically, he signals out the Koch brothers—Charles G. and David H.—who are sons of Fred C., founder of the second-largest privately owned conglomerate of oil, gas, and chemical in the U.S., of which they own 84%.[23] Described as the “poster boys of the 1 percent” constituting America’s wealthy elite, the Koch Brothers have come under scrutiny in the public eye, particularly amongst political progressives, for their funding of conservative and libertarian thinktanks which have in turn generated propaganda that has warped public opinion concerning the environment, education, campaign finance, immigration, and labor rights.[24] Punning on the pronunciation of their name, Sole raps:

It ain’t a Tea Party for you, it’s too exclusive

You do the heavy lifting, ‘cuz you used to it

Them union bustin’ coke brothers

And Forbes motherfuckers fund it

–Crude isn’t it?

Once again, the rapper calls for a critical re-evaluation of “white rage” and challenges those pushing the Tea Party platform to see that the intentions of corporate lobbyists such as the Koch (a.k.a. “coke”) brothers are most certainly not in their best interest. At the top of Forbes business magazine’s list of 400 wealthiest Americans (read: “Forbes motherfuckers”) the Koch brothers signify access to unbridled economic security enjoyed by the country’s wealthy elite from which those constituting the Tea Party, in its largely middle and working class make-up, are excluded. Charging business elites for the breakdown of a strong manufacturing sector in American cities, Sole calls them “crude” as a subtle reference to and play on words pertaining to the trade in “crude oil” with which the Koch brothers are involved. He meanwhile puns on the pronunciation of the Koch brothers’ last name, calling them the “coke brothers” as way to link the kind of “hustling” in which they are involved to the drug-running that has turned into a kind of subaltern economy[25] for members of America’s urban communities most disenfranchised by the outsourcing of industry and big business union busting.

These communities, populated in large part by racial minorities, have meanwhile become centers of criminal activity with the formation of “juvenocracies” (Dyson 1993) emerging on the heels of deindustrialization in America’s urban pockets, fueling stereotypes about black criminality (what we could call the Willie Horton Effect) and feeding into the “white rage” (read white paranoia/white anger) Sole is reproving when he spits:

You don’t visit the city

Your immigrant grandparents

Settled in

Like you scared to step

Where white flight fled

–so telling, isn’t it?

Sole thereby clues us in on the racially-fueled dynamics inherent in the large-scale migration of European-Americans from urban areas in which they were originally situated to more racially unmixed locations in the suburbs.[26] As Sole suggests, it is a fear-induced phenomenon that is symptomatic of a greater ill—not the “juvenization of poverty” (Neal 2012) or black criminality, which are symptoms themselves, but rather white criminality as it operates in a morally defunct capitalist system, a “society of the spectacle,” predicated on free market individualism and sustained by the exploitation of cheap, alienated labor abroad as well as the evacuation of labor altogether at home.

With these ills in mind, Sole continues:

I feel for you, homey, I really do

I watch my father go through it

And it’s killing my industry too

Like when I got out of high school

I made 50k, answering phonesNow robots or someone in lock-up

Process my flight home

That’s how capital flows

How the game goes

While you make devil of dishwashers

And let Goldman Sachs alone

In a show of empathy with the disaffected whites who constitute a dwindling middle class America, Sole acknowledges the fact that they, too, have been disenfranchised in their own right given the reality of outsourcing, etc., noted above. A former member of the tech industry himself as well as the son of a “blue-collar” father who owned his own welding company in Portland, ME, Sole has some personal connection to experiences of the shift in American’s economic terrain. By the same token, however, he recognizes that scapegoating migrant workers in particular (i.e. making “[a] devil of dishwashers”) and people of color in general (à la the Willie Horton Effect) is not a viable solution to the problems of unemployment in an age where the automation of human labor (read “Now robots or someone in lock-up / Process my flight home”) and an ensuing sense of social isolation have become a “spectacular” reality.

Sole ultimately shifts the burden of responsibility for economic disenfranchisement onto big business, signified in the second stanza above by the multinational investment banking firm Goldman Sachs—an alleged “white collar criminal” blamed partially responsible for the 2007-2012 global debt crisis and the virtual collapse of the real estate mortgage market. Despite the fact that Congress and the Justice Department brought Goldman Sachs under investigation and the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed a lawsuit against the company for misleading customers into buying mortgage-related security products that the company itself bet against, Goldman Sachs received a massive multi-billion dollar bailout from the Federal Reserve.[27] In light of this, Sole reminds his “white ragers” to consider the source of their despair, recalling the refrain that opened up the track:

White rage

Won’t be white saved

By white collar criminals

In white capes

Running old school border paranoia campaigns

In Willie Horton’s name

White man you need someone to blameWelfare nightmares

In vicious votes they wakeWhite man you need someone to blame

Returning to Sole’s primary concern about the issue of race baiting, “White Rage” is an incendiary response to the conservative backlash not only against Obama, who became scapegoat for the toppling government infrastructure he inherited from the Bush administration, but also against blackness, as a signifier of difference, itself. In this way, blackness comes to be associated with the non-white other who threatens the discourses of racial innocence, economic security, privilege, and the hegemony of whiteness that infuse the paranoid white imaginary—a “border paranoia campaign” which emerges out of white supremacist ideology that functions to secure hierarchies of difference along lines of class, ethnicity, gender, race, and sexuality.

On this note, Sole concludes his performance of antiracist white radical critique with a sermon by fellow white rapper Pedestrian, a.k.a. Evangelist J.B. Best, which functions to leave the work of historical redress Sole embodies unresolved. Indeed, the video for “White Rage” leaves us in the dark as the camera fades to black and a low voice in the cadence of a black preacher rises slowly to a feverish pitch. In this, J.B. Best takes Sole’s performance of musical blackness to a new height in a way that spins the white rage Sole is reproaching into a palpable black rage in the vein of Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” rearticulating her anthemic civil rights protest song—written in response to the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evans and the death of four black children (Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robinson, and Denise McNair) after a bombing of Birmingham, Alabama’s 16th Street Baptist church—in the context of the anti-immigrant fervor in the United States, realized horrifically in the attempted assassination of Democratic Arizona Representative Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords on January 8, 2011.

A polemic that pulls together the various themes resonant in Sole’s performance, the piece is worthy to be read in its near-entirety for the sake of communicating its unsettling evocation and invocation of black rage:

California has got me so upset / Texas has made me lose my rest / But everybody knows about Arizona / Goddamn Arizona / Arizona Goddamn / On the eighth day of January / In the late morning shadow of a Safeway / A strange grudge wakened on grey wings / Outspread over an adobe suburb / Where white flight had fled / And made a cold calculus of prey / In black seeds of lead and bodies left / In entry wounds so intimate they’re almost exit / And finally, yes, finally, / In blind death / For the first slaves over / Laid a curse on America […] / That when its malignant real estate market / To dead dust returned / Its last weeds and worms / Would be English first.

The rapper-cum-street corner prophet then lists a series of names signifying the “white criminals” Sole addresses in “White Rage” and concludes by indicting them for crimes against (black) humanity:

Lame memory serves subpoenas / To your marbled tombs / May that word / Your name / Not rest / In its after-life / As slur / Arizona Goddamn / No Amen

Both Sole and Pedestrian engage in what cultural critic Huey Copeland would call a “language of redress” through a rap-inflected sermon infused with a rhetoric of “reparative speech which seek[s] justice for the subjects of racial oppression.”[28] By way of this rap rhetoric, the emcees open up space for imagining the possibilities of black redemption, if not revenge, in a turn toward poetic justice that extricates blackness from criminality and condemns racist whiteness (which brought the “first slaves over”) to death in the rubble of the decay (read “malignant real estate market”)in which racist whiteness has culminated. Evangelist J.B. Best, in the vein of a fiery prophet, damns those responsible for racial abjection and the horrors of slavery as it lives on in “white rage” to an after-life of unrest, of coming face-to-face with the themselves as the collective, criminal embodiment of racism—analogized in the stanza above as a racist “slur” against (black) humanity.

That the video should end in the dark is not surprising when “read” in tandem with the words of “Arizona Goddamn”—an evocation of the memory of slavery that haunts American history like a ghost (or the “curse of the first slaves over”) lurking in the kind of pitch-black darkness that encompasses the music video’s spoken-word coda. It is out of this darkness of the past that the work of redress emerges. It is a task that remains “terminally unfinished,” as Copeland notes, “requiring constant repetition and renewal in order to keep the past alive and the present under scrutiny.”[29] Hence the “No Amen” that closes J.B. Best’s sermon, leaving its listeners hanging in an air of uncertainty about what is to come in an American racial climate still fraught by the storm of “white rage.”

It is through “White Rage” that Sole manages to turn the “hysteria of white America” against itself. He does so in a manner of Debordian critique aimed at the spectacle of white supremacy, funneling his own (white) rage against whiteness through an act of détournement. In so doing, Sole engages in a politics of anti-racist whiteness that serves to bring whiteness into visibility, strip it of its innocence, and ultimately dismantle the discourse of supremacy and privilege fixed within it.

Hip hop is indispensible to his project and Sole’s positionality as an emcee schooled in the rap game places him squarely in a tradition of black musical performance and cultural criticism rooted in a politics and history of subaltern subversion. Sole thus finds entryway into the realm of what black critical theorist Richard Iton calls the “black fantastic,” which refers to “minor-key sensibilities generated from the experiences of the underground, the vagabond, and those constituencies marked as deviant.”[30] Generated within an arena beyond the reach of the modern state, the black fantastic is an episteme that conjoins the spheres of formal politics and popular culture as a means of self-fashioning on the part of “blacks and other nonwhites” typically excluded from the realm of electoral politics.[31] In other words, it is a style of politics rooted in black cultural production which demands, as Iton says of popular culture in general, “nuance, dadaesque ambiguity, and contrapuntality [or the tension of opposition] as it resists fixedness in its moves between the grounded and the fantastic.”[32] In this, the “fantastic” is meant to signify the “‘mythic, or magical, or unbelievable’”[33] as it pertains to the black imaginary and the “underdeveloped possibilities” of emancipation situated therein.[34]

In his adroit and conscientious appropriation of musical blackness through his “skills on the mic” as a white rapper deeply informed by the “black epistemology” of hip hop culture, Sole enters into the black fantastic as a “white radical” who’s “never on sabbatical” (see “Don’t Riot“). As “White Rage” attests, Sole claims solidarity with those typically ousted from participation in “civil society” through a rearticulation of whiteness as oppositional. Indeed his is a cultural politics of whiteness refracted through a “black fantastic” hermeneutic of critical engagement with modern state aimed at unsettling its spectacular, white supremacist structure of “white rage” and privilege.

As per the critical pedagogy that E. Patrick Johnson maps out in Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authencity (2003), Sole engages in a “dialogic performance” of blackness through the black-based medium of hip-hop by locating the “(black) Other within—that Other that is always in the process of becoming” without fetishizing, essentializing, trivializing, or conflating his own and/or the “Other’s” racial subjectivity.[35] With “White Rage” as a case-in-point, Sole negotiates this terrain with prophetic, critically white candor that, through rap music, links white supremacy to the interplay of discursive structures and material conditions that reinforce it. In this way he contributes to hip hop as both an art form and a cultural movement rife with potential for crossracial dialogue and the framing of a new racial politics rooted in radical critique. And it is this very feat, informed by a conscious grappling with the racial politics of a “black art” on which he was reared, that makes Sole one of “da baddest poets.”

In positing this, I draw on Dyson’s “post-appropriationist paradigm of cultural and racial exchange” (Chennault 1998), recalling Dyson’s injunction that we must “account for transgressive whiteness”[36] and, in this vein, nuance what we mean by “abolishing” whiteness (“Do we want to abolish whiteness, or do we want to destroy the negative meaning associated with white identities?”[37]). Sole invites us to take into consideration the various ways in which whites define themselves not necessarily over and against blackness, but alongside it.[38] Underlying this consideration is a critical move toward a politics of interracial identification that has implications for the anti-racist work of critical whiteness at the same time that it opens the boundaries of appropriation by asking: How do whites and blacks co-constitute one another?[39]

With that question in mind, I echo Dyson in arguing that we must get beyond biological determinism, i.e. essentialism, in speaking of race so as to open up discursive space for the various identities/identifications within both blackness and whiteness as social and ideological constructions that are in constant interplay within one another.[40] By the same token, just as it is important to celebrate anti-racist articulations of whiteness, it is equally as essential, if not more important, to avoid centering neo-abolitionist or anti-racist white discourses at the expense of pushing non-white positionalities once again to the margins and thus reinscribing the very discursive mechanisms of white supremacy that critical whiteness seeks to dismantle.[41] Moreover, we must be wary of, as one colleague has advised me, not to “recapitulate the asymmetries structured [by] and structuring white supremacy” by “relying on the backs of blacks in order to bring [white people] to wholeness or whatever you want to call it.” Thus Dyson’s clarion call to whiteness studies scholars to “look b(l)ack” (Chennault 1998) must be taken up with great care–a tension I am not quite sure how to negotiate except by acknowledging it.

Tapping into hip hop’s possibilities as a medium of ideology critique is a key step for whites to “look b(l)ack.” In this, it is important to recognize white hip hop activists, reared on the blackness of hip hop as an oppositional politics, who offer models of antiracist whiteness by their engagement in issues that “matter to [contemporary] youth across the board,” namely: “living wage jobs, military-industrial complex, education, environment and incarceration.”[42] Sole and the work he is doing at the level of hip hop performance and activism ultimately reveals a member of the hip hop community who has taken up Chicago underground graffiti artist Upski’s call for “white hip-hop kids” to give back—i.e. “look b(l)ack”—to the cultural politics that shaped them.[43]

Bibliography

[1] See “Eminem: The New White Negro,” in Everything But the Burden: What White People Take from Black Culture (New York: Harlem Moon, 2003), 30.

[2] Ibid., 37.

[3] Ibid., 28.

[4] Gayle Wald, “One of the Boys? Whiteness, Gender, and Popular Music Studies,” in Whiteness: A Critical Reader, ed. Mike Hill (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 158. Cf. George Lipsitz, Dangerous Crossroads (New York: Verso, 1994), 53.

[5] Ibid. Cf. Lipsitz, Dangerous Crossroads, 54.

[6] “Situationist International,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, (Wikimedia Foundation Inc., updated May 3, 2014) [encyclopedia online], accessed May 14, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Situationist.

[7] Douglas Holt, Cultural Strategy Using Innovative Ideologies to Build Breakthrough Brands (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 252.

[8] Defined as the “unfair use of statements about race to try to influence the actions or attitudes of a particular group of people.” “Race-baiting,” in Merriam-Webster Online, (An Encyclopaedia Britannica Company) [dictionary online], accessed May 14, 2014, http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/race_baiting.

[9] See Sole and Evangelist J.B. Best, “White Rage (Popular Demand remix),” youtube, uploaded January 26, 2011, accessed August 27, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRHpWLgI4WM

[10] “Gabrielle Giffords,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 8, 2014) [encyclopedia online], accessed May 14, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabrielle_giffords#Immigration_and_border_security.

[11] Watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRHpWLgI4WM

[12] This alludes to a conspiracy theory linking President Obama’s 2010 six-month moratorium on deep-water drilling to the lease of rigs and ships to countries such as Brazil, where the oil company Petrobras is situated. According to conspiracy, one of the Obama campaign’s major financial backers, business magnate and philanthropist George Soros, also a well known supporter of progressive-liberal causes, has, or had, $811 million invested in the oil company. Conspiracy theorists claim that the moratorium is part of some back-handed deal between the Obama administration and Soros. As an example, see Tait Trussle, “Soro’s Oil Spill Payoff,” Frontpage Mag, June 22, 2010, accessed May 14, 2014, http://www.frontpagemag.com/2010/tait-trussell/soros-oil-spill-payoff/

[13] Recognized as the “Great Seal of the United States” used to authenticate government documents, and also found on the reverse of the one-dollar bill, the ancient Egyptian symbol of protection, royal power and good health was appropriated by the founding fathers as a stamp of approval for, and blessing of prosperity on, the formation of the United States as though divinely mandated. It has since become known as the “Eye of Providence” and is linked by way of conspiracy theory to the “Illuminati”—a sectarian group with supposed historical ties to the Bavarian Illumaniti, an Enlightenment-Era secret society aimed at opposing superstition, prejudice against women, and abuses of state power. In the contemporary context, it has, however, come to refer to something more insidious in intent: a secret organization aimed at masterminding a New World Order by planting covert agents in government and big business. See, “Eye of Horus,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 2, 2014) [encyclopedia online], accessed May 14, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eye_of_horus; “The Great Seal of the United States,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 14, 2014), [encyclopedia online], accessed May 14, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Seal_of_the_United_States; “Illuminati,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 13, 2014) [encyclopedia online], accessed May 15, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illuminati.

[14] Thorin Klosowski, “Sole Drops a New Video for ‘White Rage,’” Backbeat: Music, Culture, Nightlife, January 27, 2011, accessed May 14, 2014, http://blogs.westword.com/backbeat/2011/01/sole_drops_a_new_video_for_whi.php

[15] Ibid.

[16] See Joe L. Kincheloe and Shirley R. Steinberg, “Addressing the Crisis of Whiteness: Reconfiguring White Identity in a Pedagogy of Whiteness,” in White Reign: Deploying Whiteness in America, ed. Joe L. Kincheloe et al. (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998), 10.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Cultural theorist Richard Iton gives an extensive, intersectional treatment of the failures and fissures of welfare reform that began with Bill Clinton’s election to presidency in 1992. See “Women and Children First,” In Search of the Black Fantastic: Politics and Popular Culture in the Post-Civil Rights Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 140-48.

[19] “Willie Horton,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated April 1, 2014), [encyclopedia online], accessed may 14, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willie_Horton.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] WalterCrunkite, “Rap vs. Ronald Regan,” rapgenius, January 16, 2012, accessed May 2013, http://rapgenius.com/posts/775-Rap-vs-ronald-reagan

[23]“Political Activities of the Koch Brothers,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated April 27, 2014), [encyclopedia online], accessed May 15, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_activities_of_the_Koch_brothers

[24] Ibid.

[25] President Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy practices ushered into American cities an illicit economy of drug trafficking that became a means of survival for the materially poor in urban communities. In what was known as the Iran-Contra affair National Security Council staff member Oliver North served as the point-person for the covert sale of weapons to Iran as ransom for the release of U.S. captives in Lebanon. The second part of North’s plan involved the diversion of proceeds from weapons sales to support Nicaraguan rebel groups, or Contras, who sought to overthrow the Sandanista National Liberation Front, a group of democratic socialists named after the Augusto Cesar Sandino, who led Nicaraguan resistance against the U.S. occupation of the country in the 1930s. According to official and journalistic investigations made since the 1980s, North and other senior officials were involved in a private Contra network of drug smuggling that included Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega—all to assist the Contras in their violent revolutionary activities. This was bolstered by the distribution and sale of cocaine in a drug-running operation that spanned the coastal United States and crossed borders between it and Latin America. See WalterCrunkite, “Rap vs. Ronald Regan,” op. cit.

[26] “White Flight,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 8, 2014), [encyclopedia online], accessed May 15, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_flight

[27] “Goldman Sachs,” in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia (Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., updated May 15, 2014), accessed May 15, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldman_sachs#Controversies

[28] Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 26.

[29] Ibid., 35.

[30] Iton, op. cit., 16.

[31] See ibid., 17.

[32] Ibid., 11.

[33] Iton, quoting Toni Morrison, in ibid., 11.

[34] Riffing on Iton, ibid., 16.

[35] See E. Patrick Johnson, Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 243, 249.

[36] Chennault, in White Reign, op. cit., 319.

[37] Ibid., 317.

[38] Ibid., 320.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid., 321-322.

[41] Ibid., 323.

[42] Bakari Kitwana, Why White Kids Love Hip-Hop: Wankstas, Wiggers, Wannabes, and the New Reality of Race in America (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 173.

[43] See ibid., 175. Cf. William “Upski” Wimsatt, Bomb the Suburbs: Graffiti, Race, Freight-Hopping and the Search for Hip-Hop’s Moral Center (New York: Soft Skull Press, 1994, 2000).

Thank you for this post Rob! I’m curious though about an element that doesn’t get a lot of deep attention: physicality. One thing that always makes me go “hmm” is seeing white rap artists using the “gestures” of rap. There is a physicality that seems somehow inauthentic at times and I’m wondering your thoughts on that. Here’s a clip I found online that may interest you:

http://genius.com/discussions/29772-The-way-rappers-move-their-hands

It put me in mind of how black artists in the 1940’s were asked to perform “whiteness” in their movies. This clip of Lena Horne is classic. There’s an affectation that is inescapable:

I’m curious what you think of the physicality of “Sole”?

LikeLike

Rob, have you heard of Ariel Luckey? He merges social justice work and solidarity with indigenous communities with his scholarship and poetry. This performance, “Free Land: A Hip Hop Journey from the Streets of Oakland to the Wild Wild West,” was brought to my attention by some of the Ohlone activists and leaders I know in the Bay Area.

“my family sold their culture for American whiteness

assimilated to make it suppressing what was inside us

changed our names and our language, even our religion

in exchange for the privileges white people are given

but the cost of what was lost can not stay hidden

and now I hunger for spirituality and tradition”

— Who Am I? by Ariel Luckey

When you talk about “the possibility that appropriation can function as more than an act of cultural theft,” I am reminded of Luckey’s work in using hip hop to address his whiteness and complicity in a system of oppression, as well as identify pathways of accountability for the social and material benefits he has gained at the expense of others, specifically indigenous communities in this work.

LikeLiked by 1 person